Now live: The 2025 Canopy Report. Learn how Americans see trees. GET THE REPORT

Cruising Along the Flyways of the Mississippi Alluvial Valley

Trees are key for a stretch of river floodplain that hosts millions of migratory birds each year.

January 30, 2024

If you follow the Mississippi River as it winds its way through the United States, you will find the Mississippi Alluvial Valley.

The largest floodplain in the country, this low-lying region stretches across parts of Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Arkansas, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana. The land is home to bottomland hardwood forests that once spanned 25 million acres. Today, a mere 30% of that forest cover remains.

The reduced tree cover in this region has become an ecological challenge, as the forests support an array of biodiversity — particularly migratory birds.

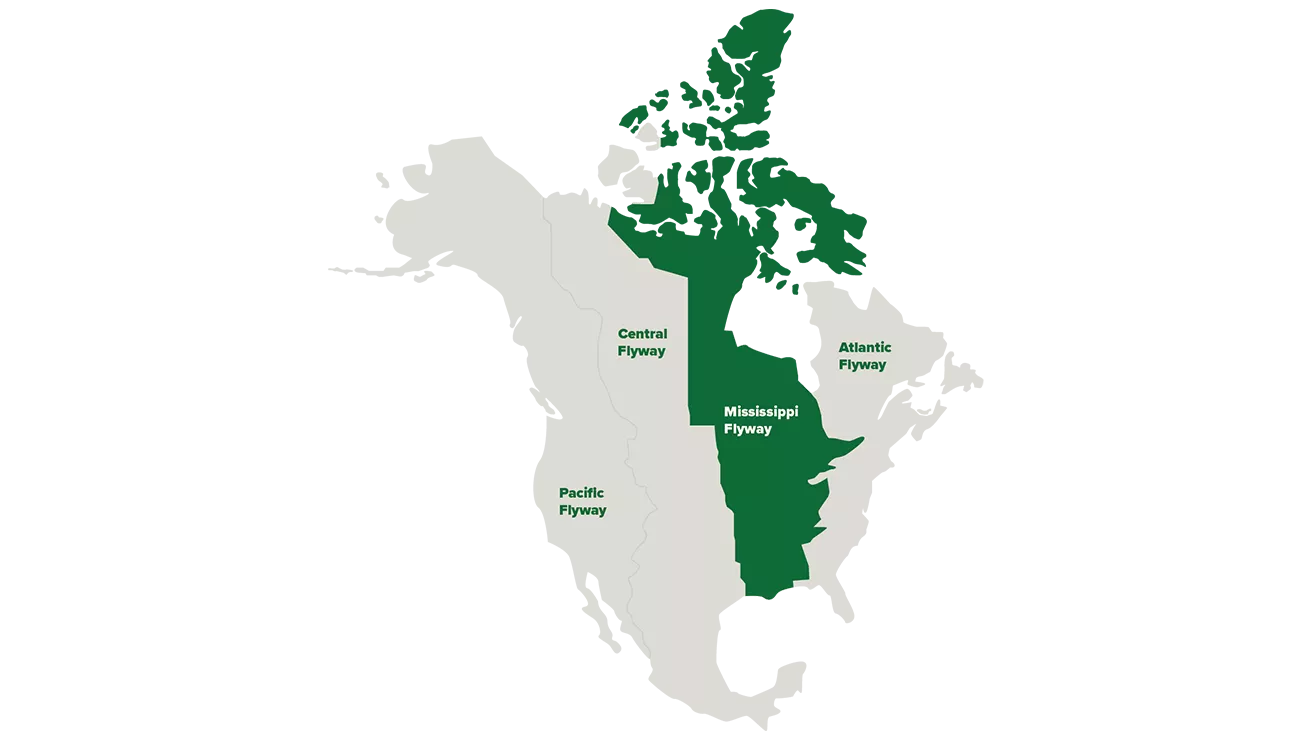

The valley is an important part of what’s called the Mississippi Flyway. This bird migration range stretches from central Canada, along the Mississippi River, to the Gulf of Mexico. And while the flyway itself is defined by province and state borders, the reality is a bit more fluid. After all, the birds don’t check the map before they take off.

According to Keith McKnight, wildlife biologist and coordinator for the Lower Mississippi Valley Joint Venture, the migratory patterns look a bit like a funnel converging on the river valley, thanks to the forested habitat there.

“That really is kind of the pinch point,” he says. “And then it funnels back out when you get to the Gulf Coast.” An estimated 40% of North America’s waterfowl and 60% of all bird species migrate to and through this region.

Waterfowl from the North Need Trees

The Mississippi Alluvial Valley is vital for the waterfowl, namely geese and ducks, traveling along the Mississippi Flyway to escape the challenging winters of the north. They follow a similar migratory window as the shore birds that travel through this area, coming in the fall and staying until the weather begins to warm.

While the geese stay primarily in the open fields, many of the ducks take refuge among the trees. Flooded bottomland hardwood forests are havens, providing a source of food: seeds, acorns, and a rich population of invertebrates — snails, crustaceans, and insects — found in the shallow water.

“You also find them there for pairing isolation and shelter from cold wind and really inclement weather. While forest habitat isn't the sole provider of habitat for waterfowl, it is an important habitat for them nonetheless,” added McKnight.

Wondering which ducks would be found in these wetland forests? Here are a few.

Neotropical birds from the south rely on those same trees

This feathered hotspot isn’t just for northern birds looking for milder winters. Large populations of neotropical birds migrate up to the region in the spring and summer months. McKnight explains that the same warming weather that causes the waterfowl to begin their journey back north brings neotropical birds in to take their place.

“They would be getting to the Mississippi Alluvial Valley in early spring, with some beginning to arrive in March. And then April, May, and June is the peak of bird nesting,” he says.

These birds use the shelter of the hardwood forests for breeding. They remain until late summer or early fall, typically beginning their journey south once a cold front begins to move in. But it’s not only because of the cooler temperatures — this weather system can actually aid in their flight back to Central America, the Caribbean, and South America.

Check out this sampling of the neotropical birds that rely on this valley’s forests for survival.

Tree Planting is for the Birds

Originally, the river valley was covered with 25 million acres of forestland.

“Our understanding of the historical valley was that it was largely a continuous bottomland hardwood forest,” notes McKnight. It was interrupted only by pine-covered ridges, deeper water habitats, and native prairie.

Today, only a bit over 8 million forested acres remain. The lack of trees has dramatically affected the ecosystem. The loss of this critical resource has resulted in a decline in habitat to support the large migratory bird populations, putting a strain on the land and the birds.

To support migratory birds — as well as the ecosystem as a whole — the Arbor Day Foundation is working with trusted local partners and landowners to not only reforest the region but also ensure that the forest stands are structured to support wildlife. These efforts are part of a larger focus on the American Southeast. The Foundation has leaned in on data and technology to identify the forests where tree planting would have the greatest impact on our world, and this region is a top priority based on that science.

“Our partnership has invested a fair amount in understanding and communicating optimal locations for reforestation and the ways to manage forests for desired forest conditions for wildlife,” says McKnight. “There's been a lot of good work done, but we need that good work to continue for these populations of birds to be secure.”

While work remains, as trees are planted and forestland is properly managed, the flyway is slowly returning to its natural state, offering respite for the migratory birds making their annual journey through the area.

The American Southeast in Focus

We plant trees around the world, but focus our efforts on key regions where trees can do the most good. In the American Southeast, we’re supporting efforts to restore longleaf pine and other native species at a massive scale. Since most of the land is privately owned, the Arbor Day Foundation is working with landowners and public entities alike to further reforestation efforts.